Archiving the internet: content for posterity

Back in January the Guardian redesigned its website, bringing a suite of small quality of life improvements to its digital audience’s experience to coincide with the launch of the paper in tabloid format. The redesign has been fairly well-received, but the Guardian – and other sites that have altered the front- and back-ends of their sites – have inadvertently stumbled upon what is becoming an acute issue around preservation of content online.

The issue is that, save for sites like PastPages and the Internet Archive, the internet is extremely ephemeral. While newspapers in print format exist in one format or another, whether in boxes stored by the paper itself or on microfiche in libraries, individual web pages can be and are frequently altered in design, copy or even deleted entirely.

It’s possible for me to find a century-old newspaper, yet work I did 8-10 years ago on the web is gone.

— Derek Willis (@derekwillis) November 13, 2014

As an example, when billionaire Peter Thiel bankrolled the lawsuit that brought down Gawker, and subsequently made a move to buy the remaining assets including the archive, it took the efforts of a non-profit called the Freedom of the Press Foundation to ensure that the archives would remain active.

So it’s worrying enough when news publishers delete or alter stories without letting their readers know – it smacks of disingenuousness and a lack of respect for their readers – but the bigger problem is one of posterity. How can readers years down the line understand the context in which the original article was delivered, and how will generations to come have access to that material if it gets deleted?

The New York Times has made efforts to counter that problem, through a new scheme primarily designed to recalibrate how its archive deals with old formats like Flash disappearing. This Nieman Lab article on the subject explains:

“‘When we started this effort last summer, it was exciting to have people involved who believed it was important to preserve the original presentation of things,’ Eugene Wang, a senior product manager at the Times, said.

“‘There was one path we could’ve taken where we’d say: We have all these articles and can render them on our new platform and just be done with it. But we recognized there was value in having a representation of them when they were first published. The archive also serves as a picture of how tools of digital storytelling evolved.’”

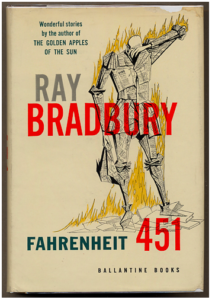

The article makes it clear exactly how challenging that process is, with the team behind the project resorting to screenshotting some pages in case the transition went wrong. But it’s a process that’s well worth the effort, particularly for any news organisation dedicated to preserving knowledge and acting in the public good. Brewster Kahle, the founder of the Internet Archive, makes the comparison to Fahrenheit 451, in that deleting that knowledge is analogous to the book-burning of that dystopian novel:

“But this role of a distributed preservation system for things that we love, it’s like the end of Fahrenheit 451, when people would be walking around and they were a particular book. I think people were walking around and starting to be particular collections.”

More efforts like the NYTs will spring up over the next few years, and will almost certainly be used in the messaging for any subscription package that offers access to an archive. But the real winner from those endeavours will be the public the publishers are pledged to serve.

enquiries@trippassociates.co.uk

Martin Tripp Associates is a London-based executive search consultancy. While we are best-known for our work in the TMT (technology, media, and telecoms) space, we have also worked with some of the world’s biggest brands on challenging senior positions. Feel free to contact us to discuss any of the issues raised in this blog.